Editor’s note: To read in this post in Spanish, please click here. Para leer este artículo en español, haz clic aquí.

We’ve gotten overwhelmed. Constant catastrophic news, from climate change to national politics, has given us thick skin: We don’t feel as much anymore. We can easily disconnect ourselves from the pain that our friends, neighbors and even family members are feeling and continue with our lives as if it’s nothing.

Yet while we put our heads under the sand, things are happening right under our nose. Raids on immigrants with and without papers have escalated, and the “Zero Tolerance” policy announced by Attorney General Jeff Sessions on April 6 further criminalizes the undocumented, ensuring that those who cross the border seeking asylum face criminal charges. These decisions are having devastating effects.

Between April 19 and June 15 almost 2,000 children were separated from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border. The government does not have enough places to house these children and has had to use tents for the expansion.

Although the president signed an executive order on June 20 that supposedly stops family separation, the reality is quite different. In fact, the order maintains the criminalization of immigrants and asylum seekers and seeks to detain them indefinitely. There is also no plan to reunite the children who have been kidnapped by our government with their parents.

To be a child of immigrant parents or an immigrant child in the U.S. in this political time is a tragedy. Fears, insecurities and nightmares limit the dreams and aspirations they can have.

In the first week of April, ICE agents in Tennessee broke a record by arresting 97 people at work simply for being Latino: Some of those arrested were here legally or were citizens. The next day more than 500 children didn’t arrive at school.

Many communities are facing this crisis head-on. NCRP nonprofit members including the Tennessee Immigrant & Refugee Rights Coalition, United We Dream, Define American, GALEO, Southeast Immigrant Rights Network, Virginia Coalition for Immigrant Rights, Hispanic Interest Coalition of Alabama and Inner City Muslim Action Network are fighting right now so that the vision of immigrants and their communities can be realized.

But the vast majority of the philanthropic sector has not invested in this urgent work. Between 2011 and 2015, 1 percent of all money granted by the 1000 largest U.S. foundations was intended to benefit immigrants and refugees – and only half of 1 percent was granted for strategies like civic participation that build immigrants’ and refugees’ power*.

I live in the heart of an immigrant community, and the majority are Central Americans. The uncertainty is palpable on the faces of these kids. To see them waiting for the school bus, you can see their sadness, fatigue, and disinterest in life.

I know them, and when talking with them you realize that they’re aware that their parents can be deported at any time. They can’t make plans for a future with their parents because there’s no guarantee that they’ll be together the next month.

Titu, a 7-year-old neighbor of mine, told me, “My mom already told my aunt that she would be our guardian if they deport her.”

And Carlitos, 13, already knows how to read legal documents and stay vigilant about his surroundings. He’s worried that his mother drives too fast and without a seatbelt; he makes sure that the car lights work and that they follow driving laws out of fear that he’ll lose his only family in this country – his native country.

Both of these children feel disconnected from everything this great nation can offer them: They can’t imagine a life without their mothers, nor can they imagine a life outside their country.

Children also experience intimidation and verbal abuse at school, but their parents fear reporting these problems for fear of deportation. This leaves the children feeling powerless, without anyone to watch over them. Instead of being protected, many of them stay quiet and resign themselves to endure.

These families dream of a solution, a change in laws that will permit them to stay to work and to transform their lives and the lives of their children. But politics and partisanship have prevented us from coming to a common sense agreement about how to meaningfully address the ramifications of immigration.

We are ruining our future, because the generation that can help this nation achieve new goals, discover new medicines or reach another galaxy is being destroyed.

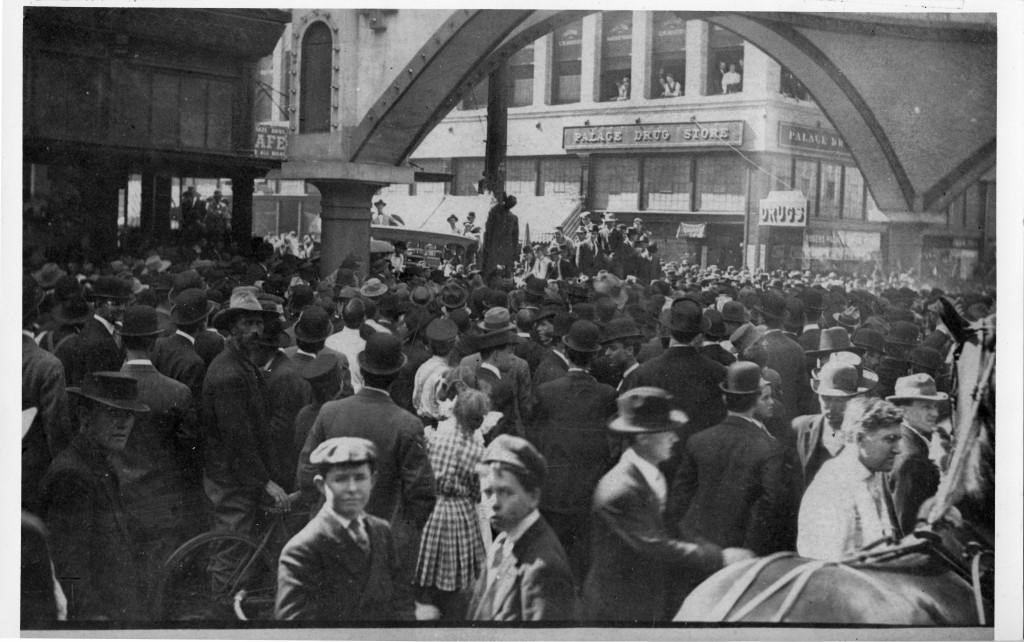

This nation owes much to immigrants; we have always been part of the history and foundation of the U.S., and we will continue to be.

The new generation will break boundaries, creeds and barriers of race and gender. We need to give them the necessary resources to get there. They have the right to dream freely about their future.

Will we wait until we lose more souls like Claudia Patricia, Gómes González and Roxana Hernández? Will we forget to dream of a better future? Of course not! We will not give up. We’ll educate ourselves, unite forces and take action.

Foundations and donors, you have a crucial part to play:

1. Listen to immigrants, respect their stories and center their vision. Remember that we are diverse, knowledgeable and already have the skills we need to win.

2. Get money out the door quickly to immigrant leaders, particularly our youth. We are fighting for our lives! We don’t have time to jump through hoops.

3. Commit for the long haul. Long-term general operating support allows us be nimble, strategic and, yes, sane. We need and deserve the capacity to think years ahead, because the roots of this tragedy will remain with us for the foreseeable future.

4. Educate yourself through attending events by groups such as Grantmakers Concerned with Immigrants and Refugees, which is holding a webinar about family separation at the border on Wednesday, June 27.

We are the adults. Let’s unite forces and make a future for these children. Our great-grandchildren will thank us.

Aracely Melendez is NCRP’s IT manager. Follow @NCRP on Twitter.

*Based on NCRP analysis of Foundation Center data.

Si el amor se enfría, encendamos el fuego

Ya estamos saturados. Tantas noticias de calamidades, por cuestiones climáticas o por situaciones políticas, se nos han hecho la piel gruesa: Ya no sentimos.

Podemos desconectarnos tan fácilmente de todo el dolor que nuestros amigos, vecinos y hasta familiares están sintiendo y seguir así, como si nada. Aunque metamos la cabeza debajo de la arena, las cosas siguen pasando bajo nuestras narices.

Las redadas de inmigrantes con o sin papeles han escalado debido a la política de “Cero Tolerancia” la cual fue anunciada por el fiscal general Jeff Sessions el 6 de abril y que criminaliza al indocumentado haciendo que las personas que crucen la frontera enfrenten cargos criminales. Esta directriz, trajo consigo efectos devastadores.

Por esta razón, entre el 19 de abril y el 22 de junio, más de 2,000 niños fueron separados de sus padres en la frontera. El gobierno no tiene suficientes lugares donde albergar a estos niños y aún han tenido que expandir los albergues de detención a través de tiendas.

Aunque el presidente firmó una orden ejecutiva el 20 de junio que supuestamente pare la separación de familias, la realidad de lo que hace es distinta. De hecho, sigue la criminalización de los inmigrantes y refugiados, y pretende retenerlos indefinitivamente. Además, no existe ningún plan para reunificar los niños ya secuestrados por el gobierno.

Ser niño de padres inmigrantes o ser un niño inmigrante en los Estados Unidos en este tiempo político es trágico.

Miedos, inseguridades, pesadillas acorralan los sueños y aspiraciones que estos niños pudieran tener. En la primera semana de abril un operativo de ICE en Tennessee que rompió cifras históricas al arrestar a 97 personas simplemente por ser latinos, ya que algunos de los arrestados están aquí legalmente o son ciudadanos. Al siguiente día, más de 500 niños no llegaron a la escuela.

Muchas comunidades se están enfrentando a esta emergencia. De hecho, miembros de NCRP como Tennessee Immigrant & Refugee Rights Coalition, United We Dream, Define American, GALEO, Southeast Immigrant Rights Network, Virginia Coalition for Immigrant Rights, Hispanic Interest Coalition of Alabama, y Inner City Muslim Action Network luchan ahora para que los derechos humanos de los inmigrantes sean respetados.

Pero la gran mayoría del sector filantrópico no ha invertido en este trabajo urgente. Durante 2011-2015, uno por ciento del dinero concedido por las fundaciones entre las mil más grandes de los Estados Unidos, fue dirigido a beneficiar a los inmigrantes y refugiados – y sólo la mitad de uno por ciento del total se dedicó a estrategias como la participación cívica que aumentan el poder**.

Yo vivo en el corazón de un área de inmigrantes, y la mayoría son centroamericanos. La incertidumbre se palpa en las caras de estos niños. Al verlos esperar el autobús escolar, se puede ver su tristeza, cansancio y deslumbro de la vida. Yo les conozco y al conversar con ellos tu puedes darte cuenta de que están conscientes que sus padres podrían ser deportados en cualquier momento. Ellos no pueden hacer planes de un futuro en el cual sus padres estarían presentes porque no hay garantía de estar juntos el próximo mes.

“Mi mami ya le dijo a mi tía que ella sería nuestra guardiana por si a ella la deporten.” Eso me comentó Titu, una vecinita de 7 años que vive cerca de mi casa.

Carlitos, a los trece años, ya sabe cómo leer documentos legales y como estar siempre atento a lo que está sucediendo en su entorno. Él se preocupa que su madre maneje rápido y sin cinturón. Asegura que las luces del auto trabajen y que las leyes se cumplan al manejar, por miedo de perder a su única familia en este país, que es su país natal. Carlitos se siente desconectado de todo lo que esta gran nación puede otorgarle, no puede imaginarse una vida sin su madre, pero tampoco puede imaginarse una vida fuera de su país.

En la escuela local, los niños cuentan de abusos verbales e intimidación a sus padres, pero estos niños se sienten sin derechos y se han quedado sin alguien que vele por ellos porque a sus padres les da miedo ir a la escuela a preguntar o reclamar, por temor a ser deportados.

En vez de ser protegidos, muchos callan y dejan pasar abusos. Estas familias sueñan con una solución, un cambio en las leyes que permitiera quedarse a trabajar, lo cual transformaría las vidas de estas familias y de estos niños. Pero la política, y los poderes de partido han impedido a tener un acuerdo común de cómo tratar con las ramificaciones de emigración.

Esta nación está en deuda con nosotros los inmigrantes; siempre hemos formado parte de la historia y de la fundación de los Estados Unidos y lo seguiremos siendo.

La nueva generación romperá fronteras, credos, y barreras de género y de raza. Tenemos que brindarles los recursos necesarios para llegar allí. Tienen derecho a soñar libremente con un futuro.

Estamos destrozando nuestro futuro, porque la generación que pudiera llevar a esta nación a alcanzar nuevas metas, descubrir nuevas medicinas o llegar a otra galaxia, está siendo destruida.

¿Esperamos hasta que hayamos perdido más almas como Claudia Patricia, Gómes González y Roxana Hernández? ¿O nos olvidamos a un futuro mejor?

¡Claro que no! No nos daremos por vencidos. Uniremos las fuerzas, y tomaremos acción.

Fundaciones y donantes, ustedes tienen una parte crucial que jugar:

1. Escuchar a los inmigrantes, respetar sus historias, y centralizar sus visiones. Recuerde que somos diversos, conocedores y que ya tenemos las habilidades que necesitamos para ganar.

2. Otorgue disponibilidad de dinero rápidamente a líderes inmigrantes, especialmente a nuestros jóvenes. ¡Estamos luchando por nuestras vidas! No tenemos tiempo para pasar a través de obstáculos.

3. Comprometerse a largo plazo. El apoyo operativo general a largo plazo nos permite ser ágiles, estratégicos y sí, sensatos. Necesitamos y merecemos la capacidad de pensar en los próximos años, porque las raíces de esta tragedia permanecerán con nosotros en el futuro previsible.

4. Educarse asistiendo a eventos de grupos como Grantmakers Concerned with Immigrants and Refugees, como el webinar sobre la situación de las familias separadas en la frontera que se llevará a cabo el miércoles 27 de junio.

Somos los adultos. Unamos fuerzas, marquemos un futuro para estos niños. Nuestro bis-nietos lo agradecerán.

**Analísis de NCRP basado en el data de Foundation Center.