Centering Asian Immigrant Refugee Wisdom

is Key to a Healthier Planet

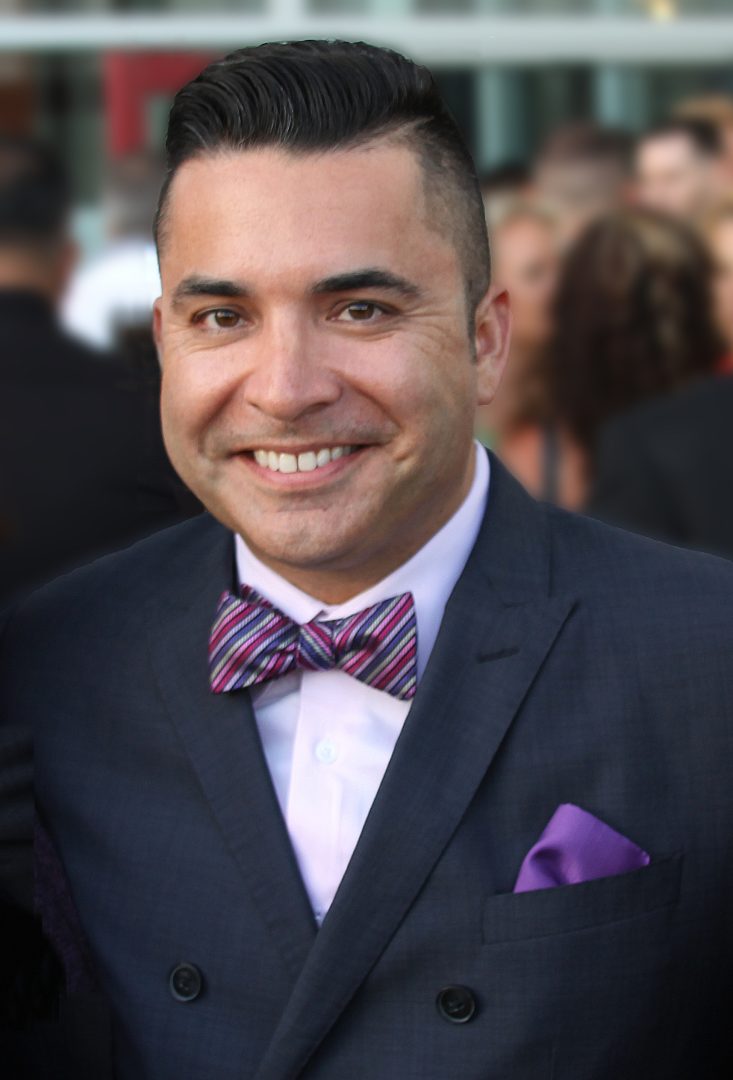

In part 2 of our Celebrating Asian immigrant refugee Contributions to Climate Action series, APEN’s Christine Cordero discusses the organization’s history and how climate funders and organizers can create a healthier world by centering the wisdom of Asian immigrant refugee peoples.

In the previous entry in this three-part series, Filipino climate justice frontline leader and Co-Director of the Asian Pacific Environmental Network (APEN), Christine Cordero spoke about the importance of changing narratives around Asian immigrant refugee communities in creating a more equitable and healthier world. In this second part, her discussion with NCRP’s Senowa Mize-Fox centers on APEN’s history and what past campaigns can teach funders and organizers about integrating the wisdom of Asian immigrant refugee peoples.

Christine Cordero: That’s a great question. Vivian, our other Co-Director, and I recently got to have lunch with one of the founders.

Senowa Mize-Fox: APEN has been around for almost thirty years now – from your perspective, how has the organizing strategy shifted as the organization has grown?

Christine Cordero: That’s a great question. Vivian, our other Co-Director, and I recently got to have lunch with one of the founders.

From its inception, APEN has been really interesting. APEN came out of 1991’s People of Color Environmental Justice Summit, which was a response to the general criticism at that time that the environmental movement was mostly about trees and white people. At that convening, there were a handful of Asian American and Asian immigrant and PIs who were like, ”Where’s the Asian immigrant refugee voice in this? And how that actually needs to get stronger for the environmental justice movement.

That was the call.

Multiracial, Multilingual, Multigenerational Placed-based Roots & Actions

Christine: We have an APEN shirt that says “rooted and resilient.” I know a lot of our communities are like ‘We’re tired of being resilient.’ However, it’s also about being rooted.

APEN from its founding was about being rooted in very specific communities that need a voice where there currently isn’t the Asian immigrant refugee voice for environmental justice. From the beginning, we knew we were a part of a multiracial, multiethnic movement. Our Black, brown and Indigenous brothers and sisters and brothers in environmental justice conversations were like, ‘Where are y’all at?’’ And we were like, ‘Cool. I guess we got the call.’

We had a call to do this.

We also wanted resiliency in the sense that it’s actually on purpose. The last letter N is for network. The intention was always to have a broader set of forces that were moving in tandem together on the intersection of Asian immigrant refugee folks and environmental justice.

We began very local with young Laotian women in Richmond. It was our Laotian immigrant refugee folks who knew that something was happening with the air and in the water there because it showed in the food people were growing and the health of family members. Many immigrant folks have a deep connection to land through farming practices and growing practices. And then we started to see health impacts in our intergenerational families, on our young women and on their children.

A multilingual warning system needed to be put in place in Richmond. Chevron would flare and the warnings would go out in English. Yet the population spoke multiple languages. So, our folks and APEN started by fighting for something very basic: a multilingual warning system. Then we started to trace problems to the root, looking at how the air was being regulated in the city. Then people start noticing a lot of that happening at the state level. You start asking ‘How do we make sure that these things don’t happen?’ And ‘Who can actually hold these industries accountable?’

At that point, APEN realizes ‘We have to do work at the state level as well.’

There were too many things being done to us without us.

Making Space for & Engaging with Needed Voices

Christine: The environmental justice movement believes in ‘Nothing about us without us,’ right? So, that being the case, we started to trace the power structure right up into where it needed to go. APEN started engaging in statewide policy because we had to, because that’s where the decisions were being made that affected our families and community. We started engaging in multiple campaigns, trying to convince elected officials of our stances and about what our communities cared about.

At some point after doing that, APEN, ‘We should be putting people who align with our values into those elected positions making decisions.’ So about 10 years ago, APEN Action started. We didn’t originally want to do voting and electoral work. But again, when you start tracking down what works, where communities need to build power and what is needed to make change, you realize that a lot of it depends on getting more of our folks engaged.

According to a 2020 NRDC survey, 77% of Asian American voters support stronger policies on climate change. The report quotes APEN, because we did an earlier report that found that upwards of 80% of Asian Americans in the state of California consider themselves environmentalists, compared to like, 40%, [overall] right? So yes, you have those of us who are connected in our histories of how our people were brought here. Those who know how our practices were in our original homelands, and when getting here, have a deep sense of connection to the environment and climate. Yet, who do you have calling up Asian American or immigrant refugee voters on environmental and climate issues?

We’re an untapped constituency that already cares about these things. That’s why we’re excited that, after decades of dreaming of this, we’re in a position to start a statewide membership by the end of this year. We currently have community bases in Richmond and Oakland and we’ll be launching LA, Wilmington and the San Pedro area.

We know that we need a statewide presence. With statewide membership, we will have a broader front of supporters really following our frontline community bases in the agenda we’re setting. We understand that even though not everybody is on that fence line, all of us are impacted by climate disruption?

If you’ve talked to anybody — and I don’t know that anybody’s denying it at this point – they will tell you that there has been an uptick, an upsurge of folks who really want to find ways that we can act on climate and environmental justice. We’re taking the approach of going bigger by starting at home. That is what it’s going to take to really build an organizing strategy.

So even on the county level, I was just telling a funder this today, we want to Just Transition the refineries in the whole state and in particular, the one that we’ve been fighting in Richmond. It’s over 100 years old. We want to Just Transition that refinery, our members want it closed. They want something else. They want an economy that actually supports the land and our people.

And so, what does it mean to dream that out? In California, we just set out some of the most ambitious climate goals, we’re going to reduce our use of fossil fuels by 90%. By 2045, like, it seems far, but that transition is really real. Then we’re looking at a $700 million tax base replacement in Contra Costa County alone. That’s one county, out of the Bay regions. What does it take to protect the social safety net? What do we want in the place of a fossil fuel-based economy?

Because we sure as hell don’t want a bunch of Amazon warehouses. We don’t want just another polluting industry. So, we’re really asking our folks, what do we want there instead?

The Chevron refinery is 2900 acres, and a good chunk of that is beautiful waterfront property. What would it look like to heal the land and the water for actual civic use for all of the people in the city of Richmond?

Those are the dreams we’re putting out there. Because at this point, what do we have to lose? Let’s do this right. Let’s look at what that transition looks like and how can frontline communities and workers be at the center of it?

The impact of our work goes beyond being local, regional and statewide. Because Californians are roughly 12.5% of the national population, what we do in California impacts the rest of the country. We try to stretch the field on what is possible. We are trying to do the most visionary stuff in California because we have the conditions to do that, which can then hopefully positively impact the rest of the nation.

It also means that when we haven’t been able to win big, it can limit what happens in other states, too. We do feel that pressure. We all do our best in the political conditions we have to stretch the landscape and lead to bigger wins.

Senowa: I love just how you went through that whole vision of what it’s like to build the new. As somebody else who is knee deep in everything. It’s inspiring to really see that vision. So, thank you so much for sharing that.

Learning & Leading with Our Culture

Senowa: How does the history and indigenous practices of Asian immigrant refugee communities show up in APEN’s work?

Christine: I mentioned the Laotian community connection in my previous example. I think the histories of colonization, and more are obviously huge and are a big contributing factor to how we approach our work.

We have to be organized not just thinking about what is culturally appropriate but what is culturally central to our communities. APEN is amazing in that. Our in-language organizers are amazing. The Laotian immigrant community we work with in Richmond speaks three different languages. Our Oakland base speaks Cantonese or Mandarin.

So, first and foremost, it shows up in our respect for how we do our organizing work. This is why we’re so excited about the untapped potential of a community and electorate who haven’t been mobilized, and the actions that need to be taken right now in order for our communities to thrive.

For our LA, Wilmington, and San Pedro area launches, our organizers are doing such a beautiful job of looking at the history of our communities in that region. A lot of it was around how our folks came to work, the opportunity to work. There’s also a long history of our communities, engaging and helping build up the infrastructure of that area. There’s also been a lot of personal investment in communities retaining a kind of cultural heritage.

And so our LA launch, is going to have a mural that honors this specific history in LA that a lot of people don’t know. We know that we’re part of a larger tapestry of BIPoC folks that have contributed and have built up the region. Our particular slice, we hope, will be additive and engaging.

So, we try to have culture and art always present. That also means the food! APEN is known for our food at our events and that’s solely from our people. Our people do not congregate without feeding each other. We take a lot of pride in this. We want to make the revolution yummy. It’s yummy. It’s good looking and it should be joyful.

We want to do a more comprehensive job of weaving this into our work. We know that it’s in our people’s practices to be communal. We have a lot of different practices in our different communities around communal support that we really want to be able to really tap into. To encourage, nurture, cultivate and retain.

It is very easy in immigrant populations to lose that sense of connectivity over time. American culture is too often about individual atomized nuclear families, which is not actually how most of our communities have lived for hundreds of thousands of years.

Senowa: Make the revolution yummy! I’m going to quote you on that forever.

Christine: Please, I’m not the only one. There’s been different versions. There’s the Emma Goldman one that’s like if there’s no dancing in the revolution, I don’t want it! Why would we leave our best stuff behind? We should lead with our best stuff. Our people have flavor. We need to bring the flavor forward!

Senowa: I know I’m not an Asian immigrant refugee, but yes, the food! But I am a Black person, and my family is from the South. You cannot meet without food.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Look for Part 3 of our “Celebrating Asian immigrant refugee Contributions to Climate Action Series,” when Christine discusses what a Just Transition to a Regenerative Economy looks like for in California, especially for Asian immigrant refugee and Hawaiian Pacific Islander peoples.