The floods come bigger and more often these days in North Carolina. On the fertile coastal plains and wetlands of the eastern part of the state, water is central to nearly everyone’s livelihood. Waterways knitted together small Native and early colonial communities and, later, nurtured a thriving textile industry. Generous rains still irrigate big industrial farms and small family plots. But in just the last two years, the mostly poor region has also borne two historic floods: Twice-a-century events that have begun arriving annually.

Hundreds of miles away in the backwoods and bayous of coastal Louisiana, history seems to be accelerating, too. The region was already saddled with environmental toxins from a petro-chemical industry that decimated the region with 2010’s Deepwater Horizon disaster. And 2016 brought the displacement of the country’s first seawater rise refugees. Water made Louisiana the jewel of colonial America’s inland empire; now it threatens whole swaths of the state.

Hundreds of miles away in the backwoods and bayous of coastal Louisiana, history seems to be accelerating, too. The region was already saddled with environmental toxins from a petro-chemical industry that decimated the region with 2010’s Deepwater Horizon disaster. And 2016 brought the displacement of the country’s first seawater rise refugees. Water made Louisiana the jewel of colonial America’s inland empire; now it threatens whole swaths of the state.

Southern communities are on the front lines of an ongoing global climate crisis, one whose threats grow in scope and magnitude each day. In many ways, Southerners have been among the first to learn what it’s like to live with a new climate – the more hostile one we have created for ourselves over decades of living outside our planetary means. More intense storms, hastening sea level rise, agricultural disturbances and other climate factors present an existential threat to Southern communities and an uncontainable, exponential one for the country. Many Southerners know this; they understand the threats and their enablers in concentrated, reactive, corporate-backed power. Although many of those same Southerners are organizing and mobilizing around a resilient and just new future, foundation investment in Southern communities does not match that reality.

In its As the South Grows series of reports, the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) and its partner Grantmakers for Southern Progress (GSP) have begun exploring the challenges and opportunities to increase equity in Southern communities. Foundations, as the data and others’ lived experience demonstrates, have for too long neglected funding the most promising structural change strategies in the South. As the South Grows is an attempt to examine the reasons for that neglect and to propose solutions:

- On Fertile Soil, the first in the series, explored Southern nonprofit leadership and the biases and misperceptions of both Southern and national philanthropists that have led to effective, leaderful Southern organizations being overlooked by most grantmakers. Contextualized in the fertile Black Belt and Mississippi Delta regions, the report pointed out the ways racism, sexism and prejudice can disadvantage some of the most investable Southern organizations.

- Strong Roots, the second report, highlighted the structural change potential that lies in investments in community-led economic development in the South, with a specific focus on Appalachian Kentucky and Coastal South Carolina. Economic transition is well underway across the South, where old industry has collapsed, new industry has blossomed and an economic system of exclusion and exploitation remain the norm.

“We will have a transition no matter what,” said Mountain Association for Community Economic Development President Peter Hille, “but if we want a just transition, we have to work at it.”

Hille’s quote refers to the difficult economic and social transition away from a coal economy that has been rocking the Appalachian South for years, but it could just as aptly be said about the transition to a new climate already underway globally.

Weathering the Storm, the latest installment in the series, continues the first report’s exploration of building power and the second’s examination of building wealth and looks closely at building resilience. There will be a transition to a new, and in many ways more hostile, climate that could result in disproportionate harm to already struggling communities.

In the South, the work to avoid a transition that results in disproportionate harm to already struggling communities is well underway. Weathering the Storm explores the intersection of economic, environmental and social systems where the Southern movement for climate resilience is growing. It will make the case that funders concerned about threats from our changing climate are missing a crucial opportunity to invest in solutions of national and global relevance if they are not investing in Southern organizations and networks.

“Speaking for myself, the notion that ‘as the South goes, so goes the nation’ is key. We’re not trying to stop ship building or oil extraction or Mississippi River operations in New Orleans. But hopefully by thinking about water management and other emergent sustainable industries, we can make the economic case for them and have proof that equity is a growth strategy.

“And if we’re able to do that here, then maybe we can do it with transportation, trade and logistics and other legacy industries in our region. And if we can do that then we’ll be a model for elsewhere in the South and elsewhere in the country and elsewhere in the world.

“It is a really interesting and privileged position to be both resident community members and strategic funders. It’s exciting to be able to be a part of these conversations and think about what the ripple effects of our work can be, and to be very rooted in knowing that we will see the changes within our own families and friends and neighbors and communities if we’re successful.”

— Liza Cowan, JPMorgan Chase & Co.

read related sections

Background

Voices from Eastern North Carolina and Southern Louisiana

The Bottom Line: Do’s and Don’ts for Greater Impact in the South

Getting Started

BACKGROUND

Although Eastern North Carolina and Southern Louisiana are in very different parts of the South, they share many of the same challenges that stem from their locations in coastal lowlands threatened by climate change. Both regions have land- and water-dependent economies such as agriculture and commercial fishing. Small farmers and commercial fishers have seen the impacts of development on the vitality on the natural resources they depend on.

Both regions are home to large, diverse communities of color with significant Black and Native communities as well as growing Hispanic communities.

The political landscape in their respective states is different, and Southern Louisiana includes large urban areas – New Orleans and Baton Rouge – while Eastern North Carolina does not. But the similarities in each region’s experience with environmental challenges brought on by climate change and extractive industries make them a useful lens through which to explore those issues in the South.

Between 2010 and 2014, foundation support for communities in Eastern North Carolina and Southern Louisiana did not meet the challenge presented by environmental threats, nor did it capitalize on the opportunities for long-term structural change that are growing at the grassroots in these two regions.

During this five-year period, only 4 percent of foundation funding to support work in Eastern North Carolina was designated for systemic change strategies such as community organizing, advocacy and policy change work. In Southern Louisiana, that number was 8 percent, but almost all of that systemic change funding went to New Orleans. Outside of Orleans Parish, just 0.3 percent of all funding in Southern Louisiana was invested in systemic change strategies.*

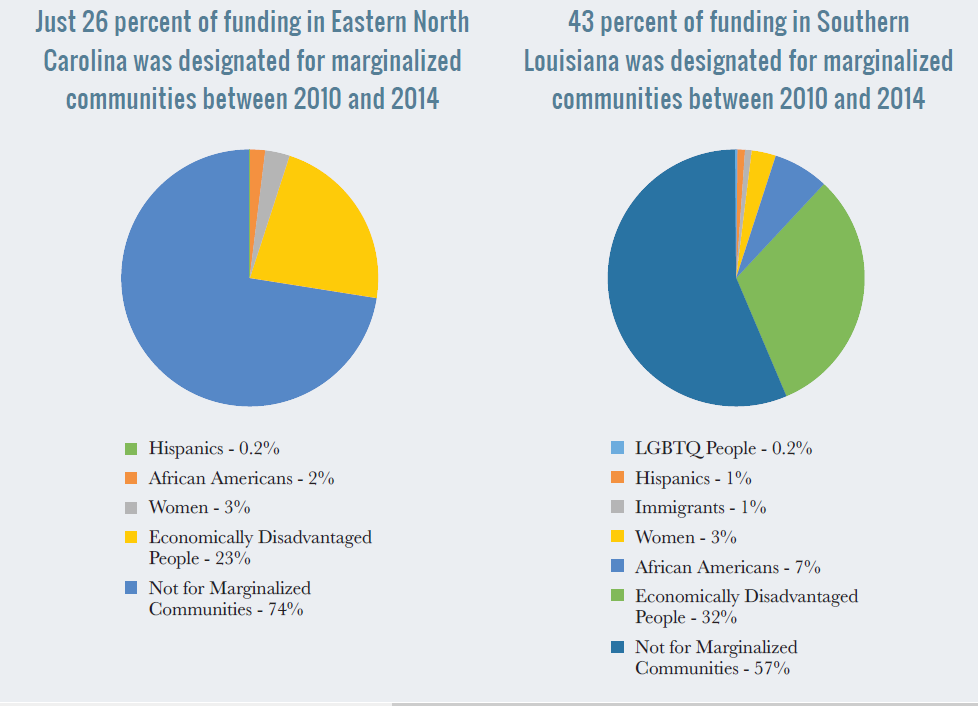

These statistics present a significant missed opportunity. In Leveraging Limited Dollars, NCRP research has demonstrated a return on systemic change investments of $115 in public benefits for each $1 invested in those strategies. Foundation support for marginalized communities was troublingly low between 2010 and 2014, too. For example, 0.5 percent of total funding in Southern Louisiana and 0.2 percent in Eastern North Carolina was designated to support Hispanic communities. In Southern Louisiana, 7 percent was designated to support African-American communities, and in Eastern North Carolina that number was just 2 percent.

In Southern Louisiana, about one-third of the population is comprised of people of color, and in Eastern North Carolina that number is nearly one-half. In both regions, about three-quarters of foundation funding between 2010 and 2014 was invested in either health, human services or education. In both regions more than half of funding was not designated to benefit any marginalized community.

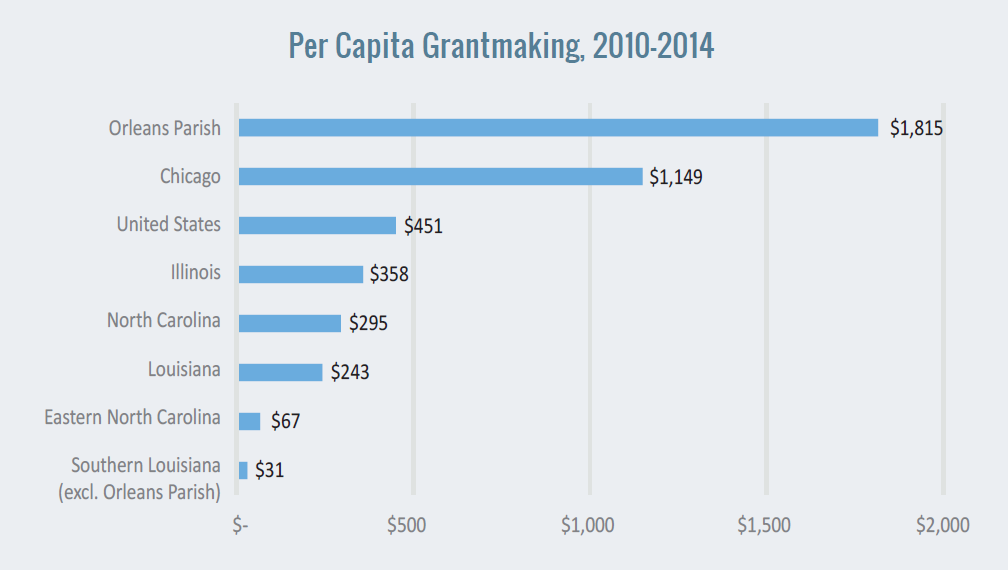

The total foundation funding flowing to these two regions lags well behind other parts of the country in per capita grant dollars.

The total foundation funding flowing to these two regions lags well behind other parts of the country in per capita grant dollars.

New Orleans has been the focus of national philanthropic attention since Hurricane Katrina, and its per capita funding shows that clearly. But Southern Louisiana (when Orleans Parish is excluded) and Eastern North Carolina saw per capita foundation investments of less than $70 per person between 2010 and 2014. Nationally, foundations invested $451 per person during the same period.

The scientific community is confident beyond doubt that global climate change is underway and that it will continue – perhaps accelerating quickly in the coming decades – for the foreseeable future. Academics and government experts have known that for some time, but predicting the specific economic impacts of climate change on regional and local levels had, until recently, been elusive.

But, in June 2017, Science magazine published a peer-reviewed study that constructs the first comprehensive predictive model of global climate change’s economic impacts on the local level. The authors concluded the South would be most negatively affected.

One climate scientist described the prediction as a “large transfer of wealth between states,” with impacts from dangerous heat, sea level rise and other effects battering the economies of Southern states and giving a slight boost to many in the north and west. More specifically, the study predicts that climate change’s negative impacts will fall disproportionately on the poorest counties in the country, many of which are in the South and many of which are home to large communities of color.

The lived experiences of folks residing and working in the coastal plains, wetlands and barrier islands of the South would corroborate this research. And especially to those who lived through any of the handful of historic tropical storms that have socked Southern communities in the last 20 years, the news matches hard economic data to difficult memories.

*Orleans Parish and the city of New Orleans are coterminous. For the purposes of analyzing funding data, NCRP has separated Orleans Parish from the surrounding Southern Louisiana region in some places because New Orleans has historically been the recipient of a large majority of funding to benefit the Southern Louisiana region.

Learn More:

As the South Grows

Photo by Bill Metcalf Photography, used under Creative Commons license.

REV. MAC LEGERTON, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, and DONNA CHAVIS, CO-FOUNDER – CENTER FOR COMMUNITY ACTION

Rev. Mac Legerton

“Hurricane Matthew [in 2016] really set us back. Robeson County, North Carolina, was hit harder by Hurricane Matthew than any other county in the nation. We’ve learned a lot about how to facilitate the empowerment of individuals, families, communities and institutions over the past 50 years, but hardly any of that learning is utilized in disaster relief and recovery. What we need is a social justice perspective and practice approach in disaster relief and recovery. As of now, we approach each natural disaster as a rehearsal for another, then another.”

These reflections by Rev. Mac Legerton, executive director of the Center for Community Action (CCA), arise out of his experience working in rural Eastern North Carolina for more than 40 years. “For low-income survivors, our present model of disaster relief and recovery magnifies every division, demoralizes every spirit, and disempowers every family and community.” said Legerton. “I have been traumatized twice – first by the hurricane disaster and secondly by the disaster recovery process itself.”

Donna Chavis, co-founder of CCA (and Legerton’s spouse), views disaster recovery from the perspective of neglect and exclusion.

“Systems aren’t in place for hearing the voices of those most affected. When people talk about wanting to get things back to the way they were, that often means going back to the way it was 20 years ago. This is because of the lack of inclusion of those most impacted by the storm. Some leaders use disaster as an opportunity to further disempower people and to try and strike down some of the gains that were made over so many decades.”

Donna Chavis

Because federal and state disaster response leaders exclude marginalized Southern communities from conversations about how to recover from a storm, they are negatively impacted by policy decisions, too. According to Chavis, when Eastern North Carolina communities responded to Hurricane Matthew many state and county officials advocated for rezoning plans that would level historic Black communities to make way for parkland and recreational areas.

While recognizing the challenges of institutional abuse and neglect in communities of color, Chavis, a member of the Lumbee tribe, is well aware of the gains made in Native American and African American communities in Eastern North Carolina and across the Rural South over the past 30 years, particularly in the area of environmental justice. She brings a deep well of experience and knowledge to her work in Eastern North Carolina. On the national level, she served on the Commission for Racial Justice of the United Church of Christ, the planning committee of the historic 1991 First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit, and chaired the boards of the Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation and the Fund of the Four Directions. She was also the founding director of Native Americans in Philanthropy.

The impacts of worsening environmental crises in the South have left a legacy of trauma that divides Southern communities and impairs their long-term climate resilience. Although these communities are not defined by this trauma, funders and organizers alike must understand it in order to begin addressing it.

Government and philanthropic responses to acute environmental crises like historic tropical storms are representative of the same sector’s responses to our ongoing, long-term climate crisis. CCA recognized this when it first organized as a nonprofit in North Carolina 37 years ago. Its proactive solution was to ensure from the beginning that CCA’s leadership would reflect the communities it served.

“The leadership at the Center had ideas about what to do but the very first active months of meetings were predominantly in church basements – countywide community gatherings where there were small group discussions. The organization was triracial in its staff in the beginning because at that time [the community] was almost exactly one-third Native American, one-third African American and one-third Caucasian. So the staff started that way, too. We had one salary, and we divided it three ways,” Chavis said.

CCA is one of the oldest multiracial grassroots social justice organizations in the South and the nation. It is situated in one of the poorest and most racially diverse rural counties and regions in the nation. Faced with the dual disasters of intensifying storms and a proposed natural gas pipeline, more and more its work is “glocal” – implementing effective and successful organization and pursuits that combine local with regional, state, national and global issues and solutions.

Despite what Legerton described as the “deconstruction” of rural North Carolina communities over the last several decades – the effects of criminalization, economic disinvestment and environmental degradation – both he and Chavis emphasized the deeply rooted resiliency pervasive in the region.

“Philanthropy can take words and use them so much that they become meaningless, and ‘resiliency’ is one of those words that’s everywhere now, especially when it comes to climate change and other disasters,” said Legerton. “But it is a word that CCA has used from the very beginning of our work. The center was started on not just the hope but on the fact that our communities are resilient. They have great potential and have gone through so many various forms of disaster and have survived through it.”

JOHN DAVIES, PRESIDENT AND CEO – BATON ROUGE AREA FOUNDATION

John Davies

The deep-rooted resilience present in Southern communities emerged in many of our interviews. Still, our nation’s comfort with racialized and entrenched poverty echoes historical struggles with racism, classism and deprivation, threatening to undermine that resilience. John Davies, president of the Baton Rouge Area Foundation, spoke about that challenge and about the disruption climate change will wreak in Southern Louisiana.

“The biggest challenge that we face on the Gulf Coast is there’s been no comprehensive response and no strategy around how to address the challenges that are being brought about by climate change, and they’re incredibly destructive,” said Davies “For example, [U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development] recently made a $50 million grant to a Native American community in South Louisiana called Isle Jean Charles to relocate the whole community to higher ground. That’s pretty disruptive. They’ve never done that before; this is the first. That’s going to happen more and more all along the coast – not just in Louisiana. So one of the biggest challenges not being paid attention to is the fact that we’re going to lose coastline and communities as a result.”

Davies went on to explain that, in the face of these existential challenges, communities in Southern Louisiana have grown closer, more trusting of each other and better able to meet the threat head-on.

“Our Coastal communities are very diverse – Croatian, Native Americans, First Nations, African American, Vietnamese, white folks. Over time, faced with the challenges that they’ve had – hurricanes, the BP oil leak – the communities have become closer and more forgiving of each other, more willing to accept each other. We’re deeply interested in that resilience dynamic.”

Community cohesion – the ability of communities to rally around a shared understanding of its challenges and co-strategize around solutions – will be essential to places across the South and across the globe that are threatened by climate change. The deepening climate crisis will present an existential threat to many communities, and divisions along lines of race, class and other factors will undermine our collective response. NCRP’s conversations with Southern nonprofit leaders indicated that they consider themselves well-positioned to build that cohesion, drawing on the region’s culture of mutual aid and relationship-oriented community organizing. But entrenched poverty, and especially poverty that disproportionately has an impact on communities of color, has and will continue to challenge those efforts.

“In general we live in a racially defined world. The parish I live in is 50-50 black and white. There is a growing middle and affluent African American class here. But there is still a dominant and very poor Black economic layer to our community. It’s ever-present and we’re hyper-aware of it; it’s just a reality of life. It strikes me that because it is such a prevalent part of our lives, we’re very comfortable with this reality,” Davies said.

LIZA COWAN, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, and ERIKA WRIGHT, VICE PRESIDENT GLOBAL PHILANTHROPY – JPMORGAN CHASE & CO.

Erika Wright

Southern communities have the opportunity to respond to climate change threats with coordinated planning processes that bring together government, business, community-based organizations and residents to ensure the voices of marginalized communities most impacted by environmental challenges are not excluded from these conversations.

Representing the philanthropic arm of a bank with a large footprint in the region, Liza Cowan, Erika Wright and their colleagues at JPMorgan Chase are in a unique position to bring diverse partners together around a vision for an economic future where opportunity is available to all Louisianans, regardless of race or class. Though not specific to climate resilience, the foundation’s work often involves supporting that planning process and ensuring community voices have strong representation.

“Certain voices have historically been excluded from certain conversations be it intentionally or unintentionally,” Wright said. “I think New Orleans is actually an interesting case study for this in that there are a number of high-capacity nonprofits led by people of color. There are a lot of people of color in positions of leadership within city government. And yet there is still a challenge around ensuring that voices that are truly representative of community concerns are at the table.”

Wright explained that representation within the nonprofit sector and especially in cross-sector collaboration is challenging, but folks in Southern Louisiana are gaining practice doing it well.

“Once you have new community voices in the room, you have to navigate an additional set of needs and constraints. You have to be responsive to an additional set of concerns. While it’s an ongoing challenge in [the region], I would venture to guess that many of the tables where I sit include more representation by people of color and community organizations than in other cities. I think we’re probably further along than we get credit for, but not as far as we need to be. The experience of Katrina really did help build out our civic capacity to implement collective visioning and co-creation.”

Wright and Cowan are not the only folks in Southern Louisiana who described a marked shift in the quality and tenor of nonprofit-government-business collaboration since Hurricane Katrina. But the sense of emergency that often accompanies climate resilience collaboration, especially in light of the real and urgent physical threat to already vulnerable communities like Isle Jean Charles, can be a challenge.

“In the post-Katrina environment, there is this sense of urgency,” Cowan explained. “After the storm, we had to build back, we had to recover, we all wanted to get things moving again as fast as possible. We had federal money that we had to spend by a certain deadline. And building a robust engagement process – navigating amongst different perspectives – that does take additional time and resources. Urgency is important and laudable. But at times that sense of urgency can preempt a more robust engagement process.”

JPMorgan Chase’s work in Southern Louisiana has evolved through their engagement in the Greater New Orleans Funders Network. In 2015, around the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, JPMorgan Chase and several other regional funders co-founded the network out of a desire to better align investments in Greater New Orleans for long-term change.

“Equity and inclusion are the underlying core values of the Greater New Orleans Funder Network and that runs across our investments at the action table level,” Wright explained. “JPMorgan Chase has co-chaired the equitable development table at the network, specifically to make sure our investments are aligned with bringing greater economic prosperity in the communities where we’re investing and ensuring we’re actually closing disparities.”

One of the network’s greatest assets is the opportunity it provides grantmakers like JPMorgan Chase to deepen relationships with local and national funders who bring to the table a strong analysis of the ways race, class, gender and other factors impede equitable economic growth in the region.

“Having foundations like the Ford Foundation and Foundation for Louisiana sitting at our table – a local and a national foundation with equity as a guiding principle in their work – has been huge for us. It gives us another lens to look at our investments and make sure we’re aligned with that stated value. In the South, we don’t often get credit for thinking about or wrestling with equity in the same way as folks nationally, even though there are folks locally doing that work like Foundation for Louisiana.”

The role of corporations in the marketplace can complicate any narrative about corporate philanthropy. Cowan said JPMorgan Chase Foundation’s philanthropy and their corporate responsibility work is guided by a central value: Equitable growth is the best, most sustainable way to increase prosperity – in the South and nationally.

“That work hasn’t just been happening at a network level,” Wright said. “It’s been happening internally for JPMorgan Chase too. While I think our investments in the region have definitely been influenced by having relationships with those other funders, we’ve been thinking about our own internal model and how we move toward equity and inclusion for a while as well.”

“We’ve been really intentional about continuing to sit at the table with folks who are not necessarily investing in underrepresented populations and being the voice that says ‘Why don’t we invite these folks here?’ and ‘How is this strategy addressing the disparities that we know exist because we have funded the data that shows it?’ We’ve been intentional about saying ‘OK, who are the organizations that are working with women, working with people of color?” Wright said.

At the same time, the threat posed by climate change in Southern Louisiana is an opportunity for the region to prove the feasibility of a regional response to coastal crises and to prove the centrality of equity and inclusion to any climate change funding strategy, Cowan and Wright pointed out.

“Because of that interconnectivity between and among [Louisiana communities] because of the bipartisan agreement around the coastal master plan, because of the funding available and because of our long history of working on the coast and having to manage living with water and wetlands, we have this asset in terms of [the region’s] knowledge that can be transformed to be a knowledge-based export industry to other communities around the world that are facing this threat,” Cowan said.

As its philanthropy has evolved in recent years, JPMorgan Chase has strived to deploy the company’s resources – people, data and partnerships – to ensure greatest impact in line with values of strategic philanthropy.

“From our perspective, the emerging water management industry represents a huge opportunity and one that could increase or significantly decrease disparity in the South,” Wright said. “If we can be ahead of the game in thinking about how we train a workforce or prepare small businesses to address some of these issues, then we’re not only addressing environmental concerns, but we’re also addressing economic concerns. But if the coast disappears, it won’t have mattered what we did or didn’t do.”

Read these practical tips to boost your philanthropy in the South:

Do’s and Don’ts

4 Recommendations to get you started

Updated 2/5/2018 to correct spelling of Naeema Muhammad’s name.

NAEEMA MUHAMMAD, ORGANIZING CO-DIRECTOR – NORTH CAROLINA ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE NETWORK

Naeema Muhammad

Naeema Muhammad and her colleagues at the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network (NCEJN) understand how and why local private and public sector leaders often exclude grassroots environmental organizations from conversations like the ones Liza Cowan and Erika Wright spoke about. As heirs to the legacy of longstanding environmental justice organizations in Eastern North Carolina, NCEJN represents the potential for building a diverse, climate-resilience movement that builds the power of people to advocate for themselves.

NCEJN has grown out of a people-of-color-led movement in North Carolina to emphasize the disparate impacts of environmental challenges in Black, Native and Hispanic communities. Their focus on protecting people and communities with the least wealth and power in the state has often been met with intransigence and neglect by more powerful nonprofit sector actors, elected officials and business representatives.

“The problem has been getting the other parties to the table in a way that they would look at anybody in Eastern North Carolina as their partner,” Muhammad said. “Businesses and government [representatives] really don’t see the need to work with communities. So they don’t necessarily come to the table to take part in a working relationship to resolve these issues. When we try to [bring them to the table], what we’ve seen as a matter of fact more than anything else is that they try to pit communities against one another.”

Muhammad went on to describe a specific example when government and business representatives who ought to have been collaborating with community partners – like NCEJN – instead sowed division.

“One of the main issues that we’ve been addressing for over three decades is our animal feeding operations,” Muhammad explained. “Government and industry have been a constant source of challenges for the communities fighting that issue. The industry is constantly telling the contract growers that we are their enemies and we’re trying to put them out of business. But we have never ever advocated for any of those businesses to be shut down. We always say what we want is for them to clean it up and become a better neighbor.”

Commercial agriculture has deep, long-term negative impacts on environmental and public health in Eastern North Carolina, but messages like the one in Muhammad’s example resonate in small communities where agriculture is a major source of stable work. Compounding that challenge, Muhammad explained, is the extent to which commercial agriculture (and other industries with harmful environmental effects) have captured the levers of policy and regulation.

“The industry has government so deep in their pockets, so we can’t get much help from government either even though the examples [of harm] have been made very clear. That’s the source of the problem; it’s the industry’s money. And it’s spread so far and wide in North Carolina that it just outweighs almost anything that you could try to do. But we haven’t given up and that’s the key.”

The NCEJN’s perseverance has earned it the respect and attention of bigger, better-resourced environmental groups that have shifted their focus to address the human costs of environmental degradation and climate change. But those large environmental groups’ newfound solidarity warrants close examination, added Muhammad.

“Historically the big green groups never included the human cost of environmental issues or preservation,” said Muhammad. “But then everybody started jumping on the climate change bandwagon because that’s where the money was. Then [big green groups] started calling on NCEJN because we had been talking about climate change in relationship to environmental injustice. But [the big green groups’] interest was not sincere and you could see that. They still were not truly looking at the cost of climate change [for marginalized communities].”

In the course of researching this report, Muhammad and NCEJN were not the only Southern environmental justice groups to raise concerns about the depth of larger environmental organizations’ – funders and grantees – commitment to the justice part of the work at hand. And their concerns carry a rich history of self-determination and grassroots activism that began in the South.

The modern environmental justice movement – with its focus on disparately impacted communities and on the power-building necessary in those communities to achieve lasting impact – has some of its deepest roots in the South. In fact, scholars of the movement’s history locate its origins in Eastern North Carolina. In the 1970s, the mantle of “environmentalism,” which had historically been associated primarily with middle- and upper-class white activists, was claimed by residents in Warren County, North Carolina.

The state of North Carolina proposed a toxic waste disposal landfill in the county, which was 75 percent Black and ranked 97th out of North Carolina’s 100 counties by GDP. Residents organized, deployed tactics and rhetoric learned in the Civil Rights Movement, and successfully halted the state’s plans. The systemic pollution and exploitation of poor communities and communities of color gained national attention, and the modern environmental justice movement was born.

Groups like NCEJN, CCA and close partner organization Concerned Citizens for Tillery are the direct heirs of that pioneering work. But, as Muhammad pointed out, too often larger, better-funded environmental organizations either under-invest in Southern organizations that defined (and continue to define) the modern movement, or they engage with those organizations cynically out of a desire to exploit their well-earned reputation to the big green groups’ advantage.

“Funders say they want to fund social change, but if they’re not putting the money where the problems are, they must not really want to fund that kind of change,” Muhammad said. “The big green groups can get any amount of money that they request, but the groups that are on the ground – the ones that are down in the trenches – we get the crumbs off the table.”

further reading: NCEJN in their own words

MIKKI SAGER, DIRECTOR, RESOURCEFUL COMMUNITIES – THE CONSERVATION FUND

Mikki Sager

Despite the challenges organizations like NCEJN face, the South is home to high-impact intermediary organizations that leverage their expertise and, more importantly, their deep relationships with grassroots organizers to drive more resources to those groups “down in the trenches.”

Mikki Sager, director of The Conservation Fund’s Resourceful Communities program in North Carolina, spoke about the impact of investing in capacity and building a resilient grassroots nonprofit infrastructure to mirror the resilient communities necessary to meet the climate change challenge. Part of Resourceful Communities’ success can be credited to Sager’s nimble way of connecting issues larger foundations have prioritized back to the South’s natural resources. At the center of this holistic and intersectional understanding of environmental preservation is the power of land to restore communities, right past wrongs and build wealth, power and climate resilience.

=“Environmental funders are the few folks in the philanthropic sector that are investing in rural places and they often give big chunks of money to buy land,” Sager said. “One of my colleagues made a map of the biodiversity hot spots and the [USDA-designated] persistent poverty counties. Not all biodiversity hot spots are home to the persistent poverty counties, but persistent poverty counties are consistently home to biodiversity hot spots.

“Biodiversity is threatened not just by environmental stress but by the degradation of the environment because of the persistent poverty, so my plea to funders would be to help people gain ownership of working land, like for community-based agriculture. Conservation groups are really good at buying land, so we can buy land and help communities build wealth, build power and build resilience with it.”

Southerners’ connection to the land is a deeply held regional tradition, and capitalizing on the productive potential of land to benefit all Southerners is at the root of Resourceful Communities’ partnerships with funders who may not otherwise prioritize environmental funding. It also means partnering with traditional environmental funders to invest in innovative community economic development strategies as a means to protect ecosystems.

“At the grassroots, people understand the power and the possibilities in owning and controlling land and economies. What we have done and are doing is leveraging conservation tools to increase land ownership by low-income households, communities of color and tribal communities. We are also supporting community economic development, small business development, community-led health programs, food sovereignty and helping rural and Native communities advance family income equality.”

Sager tied Resourceful Communities’ work back to a long history of environmental racism whose negative impacts will be amplified by our changing climate.

“There are these very fundamental environmental issues particularly around land and water in the rural South,” Sager said. “Part of the reason poor rural communities in the South are going to be more disproportionately impacted [by climate change] is because, historically, society relegated poor people and people of color to the flood plain. We have to understand the environmental issues but we also have to take into account the social and economic injustices and the related impacts.”

Resourceful Communities is a grantmaking intermediary organization. Sager and her staff help grassroots organizations across the South –especially in North Carolina – access funding and capacity-building tools and support. They also do it on those organizations’ terms, making sure the philanthropic investments do not overburden organizations with onerous requirements and restrictions and that capacity-building tools are tailored to their needs. Resourceful Communities describes it as a triple bottom-line approach.

“What we do is we say ‘Tell us what you need money for, then tell us what you’re going to do that’s going to help the economic, social justice and environmental conditions in your community improve,’” Sager said. “And we are re-granting to get the money to them – up to $15,000 grants, often to groups that are too small for most funders to justify giving grants to. We use a three-pronged strategy: We provide the grants and capacity building work, which covers everything from how your board operates, to project planning and fundraising, whatever they need, and also a lot of connecting people to each other, to resources, to funding.”

Resourceful Communities’ approach gets crucial philanthropic capital to underinvested parts of the South, and it attracts other funders to the table. By building capacity, investing in grassroots organizations and connecting those organizations to strategic partners and other sources of funding, Resourceful Communities is building a resilient “triple bottom line” nonprofit ecosystem in an area where resources for such an ecosystem have historically been scarce.

“What we have seen over the years is that communities have been able to leverage an average of $12 to $16 for every $1 we invest through small grants,” said Sager. “That includes additional funding that the groups have built their capacity to access. It includes funding that we have been able to help bring to the community, and it also includes in-kind contributions. We saw a long time ago that people [in rural communities] were getting all kinds of work done, but they were not tracking or documenting the in-kind contributions of their time, supplies and all they put into improving their communities. The amount that people put into helping themselves is a really important indicator of resilience.”

The prevalence and real value of mutual community aid, emphasized over and over in our interviews across the South, makes philanthropic investment in Southern communities high-leverage investments.

Sager shared one of Resourceful Communities’ many stories of impact. During post-hurricane recovery in Sampson County, North Carolina, the federal government funded a project to clear a critical waterway of fallen trees and other debris. The debris had caused damaging floods, especially on land where the Coharie tribal members live. But the recovery project received funding to clear debris only on parts of the river adjacent to white landowners. Resourceful Communities partnered with the Coharie to connect them with the North Carolina Forest Service, which invested $6,000 in Coharie-led recovery work.

The tribe bought equipment, and by restoring the waterway, which has significant cultural significance for the community it avoided further damage to its land and helped the young people who worked on the project gain valuable skills and reconnect with their heritage. After three years and $20,000 total in grants from Resourceful Communities and support from the University of North Carolina American Indian Center, the Coharie Tribe recently secured a $250,000 contract from the North Carolina Department of Agriculture to continue the work with the potential for developing it into a workforce training program.

Sager and her colleagues at Resourceful Communities bring a deep understanding of the structural issues that will exacerbate climate change’s impacts on Southern communities to their work. But another crucial ingredient in their success has been their capacity for high-impact, high-leverage intermediary re-granting that is done with integrity and equity in mind.

When asked what makes a good Southern intermediary organization, Sager provided a few key points:

- Representation: “We have more authentic relationships with communities when they can relate to our staff. The majority of our RC team members are people of color, grew up in low- and moderate-income households and have a broad range of skills and expertise.”

- Integrity: “We are committed to working in equitable partnerships with communities, sharing the resources and leveraging the access we have as a national nonprofit.”

- Multi-Issue Strategy: “Our partner communities are dealing with multiple issues so the triple bottom line approach helps them address multiple issues with a single funding source.”

- Equity: “You need team members who understand power, privilege, race, class and equity and who understand and are willing to address pervasive institutional racism.” And you have to be willing to use an equity lens to evaluate your work, especially to take a hard look at your grantmaking and where your other resources – like funding and staff time – are going.

As an intermediary in close relationship with funders and grassroots grantees, standing at the intersection of economic, social and environmental justice, Sager offered a sage perspective on how government, the philanthropic sector and the communities both serve will need to come together around a shared understanding of the climate challenges Southern communities will face in the coming years.

“In my experience, elected officials are pretty much saying ‘Pfft, I’m not going to worry about this. [Climate change] is not going to happen for 70 years, and I’m not worried about running for office 70 years from now,’” she said. “And when the environmentalists have meetings about climate change, they often don’t invite community leaders and activists.

“But we’ve found that, if you bring together community organizers and activists [with environmentalists and elected officials], activists are the ones who say ‘We need to be talking to the kids, to the schools, organizing and educating our communities [about the threat] and the environmentalists and elected officials get a new perspective.’ The community leaders and activists get right to the heart of it; as they say ‘Our young people are the ones who are going to inherit this mess, what can we do right now?”

And, she noted, “There is great power in connecting communities and building relationships, especially among peer community leaders. Our partners are already actively engaged in things that are now having impact on the effects of climate change – the kinds of jobs being created, parks, education, where and if development happens, etc.”

What Sager and her peers understand is that climate resiliency for already marginalized communities is an urgent need and that those communities have the skills and the leadership to build that resiliency. But few funders have met that potential with the investments to make it a reality. One foundation that has begun to invest in a holistic understanding of climate and community resilience specific to the threats faced by Southern communities is The Kresge Foundation.

Related Reading:

As the South Grows: On Fertile Soil

As the South Grows: Strong Roots

CHANTEL RUSH, PROGRAM OFFICER, AMERICAN CITIES PRACTICE – THE KRESGE FOUNDATION

Chantel Rush

The Kresge Foundation, which began investing in New Orleans in the 1950s, significantly ramped up its contribution in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Beyond supporting disaster recovery, the foundation has focused on expanding social and economic opportunities for New Orleanians. Today, the foundation finds itself looking to increase its impact on the city, including by investing more deeply in climate resilience strategies.

“Between 2005 and 2016, The Kresge Foundation invested over 30 million grant dollars in New Orleans. Throughout this time, we provided $13 million of funding for disaster recovery,” said Chantel Rush, program officer with Kresge’s American Cities Practice. “We supported a diverse set of nonprofits ranging from public health and community development to creative placemaking. Under the watchful eye of Lois DeBacker, managing director of our environment program, we also developed a robust portfolio of investments supporting climate resilience in the Greater New Orleans region.”

Post-Katrina was a critical time for the region, and the money that came was large in scale and highly responsive, Rush said.

“As we move forward, we see two opportunities: externally, for foundations and nonprofits working in common areas to align their work for maximum impact; and internally, at Kresge, to ensure our investments are connected, structured for maximum cohesion and aligned to provide targeted, focused support that moves the needle on critical issues.”

New Orleans has been the focus of attention for many national foundations since Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and Rush was not the only person to mention an opportunity for more coordination among funders. Foundation interest in New Orleans has run the gamut: education, economic development, arts and culture, housing and infrastructure have all seen philanthropic support in the years since Katrina, with all areas still facing challenges.

The Kresge Foundation is engaged in the city for the long-term, and their perspective on the successes and challenges of the post-Katrina philanthropic response as well as partnerships with organizations on the ground has led them to a specific investment strategy.

“We’ve been making impactful but distributed investments in New Orleans,” Rush explained. “We are thinking now about how we can be even more targeted. And where we think there is an opportunity for our programs to align and work at the intersections is around the idea of climate resilience.”

Climate change will bring more severe storms, more intense rainfall, more days of extreme heat and new tropical diseases to New Orleans, Rush noted.

“Flooding is a critical problem now and a growing risk as climate change progresses, posing in some cases even an existential threat for low-income people who live in New Orleans,” she said. After spending a year speaking with members of philanthropy, government and community organizations in New Orleans, Kresge believes that there is an opportunity for the philanthropic sector to do much more.

“Over the next few years you’ll see [Kresge] invest more deeply in climate resilience [in New Orleans].”

The concept of resilience is responsive to the region-wide understanding that climate change will challenge individuals, communities and systems in ways yet unseen and still unknown.

Rush went on to outline her understanding of the multifaceted concept: “Resilience involves the capacity to manage shocks and stresses and move toward a preferable future. It requires urban leaders to rethink the systems – both technical and human – that meet their communities’ basic needs. It requires practitioners to work across disciplines and sectors and to become comfortable making decisions despite uncertainties. Value judgments are inherent in resilience work: What systems and places do we seek to make more resilient and for whose benefit?”

Climate change resilience begins on the individual and family levels with building assets that can help secure a vulnerable family’s basic needs under challenging circumstances. At the community level, climate change resilience will require building community voice and power, so residents can advocate for their needs and broadcast their perspective as society mobilizes to meet the climate change challenge.

It will also require community cohesion – that sense of linked fate that comes from a shared understanding of Southern communities’ past and future – so that power can be built from within marginalized communities, instead of being diminished by outside forces.

At the systemic level, if equitable results are to be achieved, it will require a flexible, responsive infrastructure of public and private sector entities that recognize the fundamental need for social inclusion in resilience decision-making.

Climate change resilience will also demand a resilient nonprofit sector. Rush pointed out.

“Civic infrastructure is key: organizations that are well-networked and well-resourced. After Katrina, money came into the region but many individual nonprofits are still experiencing financial pressure and have an opportunity to better execute on their potential.”

COLETTE PICHON BATTLE, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR – US HUMAN RIGHTS NETWORK

Colette Pichon Battle

In spite of the challenges faced by nonprofit ecosystems in the South, Southern communities and their leaders are forging a cross-sector movement for environmental and climate justice that has the potential to move the whole region – and the whole nation – forward. Colette Pichon Battle, executive director at the US Human Rights Network, saw for herself the potential that lies in healing, reconciliation and responsive decision-making in her time as director of Gulf South Rising (GSR), based in Southern Louisiana.

A native of New Orleans, Battle spent more than a decade helping build the power of marginalized communities across the Gulf Coast to respond to climate threats. GSR is a regional movement created to spotlight the disparate impacts of climate change along the Gulf Coast. Among other accomplishments, GSR built on the leadership already present in communities most affected by climate change in the Gulf Coast region and created new leaders, shifted the regional narrative among grassroots organizations from climate resilience to resisting unjust systems that support environmental injustice and established a community controlled grantmaking fund that continues today.

In 2015, the 10th anniversary of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, GSR released its final report. The document outlined the outcomes of years of organizing and articulated a path forward for communities threatened more each day by rising seas and other environmental challenges.

The key infrastructural asset that propelled GSR forward was the initiative’s deep roots in communities who had been and would continue to be most impacted by environmental injustice. In a series of people’s assemblies held over five years across the Gulf Coast, GSR generated a strategy document that continues to guide their work. The assemblies began five years after Katrina and concluded just a few weeks before the BP oil spill.

The nonprofit infrastructure in the Gulf South had at that point “begun connecting the dots around climate, race and pollution, but they wanted to find out what the people wanted to be done – what are the people’s priorities?,” Battle explained.

Central to GSR’s success was the initiative’s ability to turn reactive energy into a movement – to transform what had seemed before like localized crises into a regional challenge.

“Our role was to listen in the assemblies to the people’s concerns, and then to work to broaden and deepen communities’ analysis of climate and extractive industries. Because we’re not just dealing with ecosystem impacts that expose us to more climate crises. We’re dealing with an economic system that’s been in place since the removal of Native people from the land – since slavery. We had to outline the distinction between extractive industry and extractive economies which is much broader.”

Extractive economies are built around “big, unaccountable institutions that take from the land, poison the people, and then get some of the largest profits in the world,” Battle continued. “They build power by marginalizing communities.”

The extractive economies frame was potent for GSR’s work, because not all parts of the Gulf South could relate to Southern Louisianans’ experience with extractive industry; in places like Southwest Florida no such industry exists. The broader frame of extractive economies could better apply to the challenges communities across the region had experienced with educational systems and mass incarceration, for example.

In addition to aligning around a shared understanding of the Gulf South’s challenges, GSR responded to one of the needs communities frequently identified when they asked: collective healing and reconciliation.

Environmental injustice in the South is built on decades of communities being neglected and outright targeted for marginalization. The extractive process Battle described whereby the powerful take from the land, poison the people and reap a profit has left a long shadow of trauma in many Southern communities. Battle explained why foundations interested in investing in the South must reckon with that reality.

“It was our Black community leadership in New Orleans who have nothing to do with the nonprofit sector or the movement language who asked for healing,” Battle said. “When we did people’s assemblies and asked them what it is they needed, they said ‘We need to heal. And if we don’t heal, we won’t get anywhere.’ If we don’t heal ourselves, our relationship with our creator, our relationship with our neighbors, our relationship with the earth, we are in for eradication.

“It’ll be climate eradication for us on the coast. It might be war and famine for folks elsewhere. It’s gonna be one of these storms that takes us out, we know it. This collective healing is the only right first step to anything that’s going to last. Movement work is long, it’s deep, it’s rooted in trust and it’s rooted in connection. And you can’t get trust or connection or longevity without some real attention to healing first.”

When funders fail to understand and respect this dynamic, their Southern investments fail to meet their expectations, Battle said.

“If you take a step back you realize the entire region is built in and rooted in trauma,” Battle said. “It’s that trauma that is the black hole that funders keep running into. ‘The return on our investment of $100,000 dollars is just not what we’d see in New York or California?’ And that’s true, because half of what people do when they get resources in the region is heal and rest so that you can now do the work that you’re finally funded to do.”

That trauma does not mean that Southern social change leaders are not equipped to accomplish amazing things, Battle continued. The shared history of extraction and exploitation is what makes Southern relationship-building, and therefore movement-building, possible.

“I get frustrated when I hear funders say ‘Why do we have to invest so much in Southern infrastructure?’ Well, so much has been extracted. The South built the nation’s wealth, and as the South goes so goes the nation.”

What infrastructure does Battle see in the South now?

“A region with a shared history that connects people: the history of slavery, oppression and rebellion. There’s one thing people in Mississippi can know about people in Alabama without having to even talk to them, and that’s ‘You survived and we survived. We’re both still here because we both have survival methods.’ Somewhere else they might see someone and say ‘Oh, you’re here.’ But when I see someone in the South it’s a different acknowledgement. It’s ‘We’re still here.’ It’s a collective ‘we.”

“If you look at the USDA’s map of persistent poverty counties, 91 percent are in the South and Appalachia, the rest of them are in the Southwest and in Indian Country, all places where people lost control or ownership of land,” said Mikki Sager of Resourceful Communities. “In the South, many of those counties are where former slaves were dispossessed of land. In Appalachia, they might own their land, but the mineral rights were sold for pennies generations ago, which often leads to land loss and dismantling of communities.”

Historically, poor people and people of color in the South have forced to live in flood plains, Sager said. Thus, poor rural communities in the South will be disproportionately affected by climate change.

“How can we help people gain ownership or increase ownership of land that’s not at risk? Landownership is key to building power, to strong economies and to resilience.”

But to have resilience there needs to be something from which to build wealth and power, she said.

“We have to build that base of landownership, of land that can be used. Land that’s not going to be flooded out by 100-year floods, land that’s not going to be underwater in the next couple of years. Land and water issues are fundamental in the South.”

Climate change presents an exponential and existential threat for people across the South – and for the nation more broadly – but foundation grantmaking to date does not reflect that reality. Southern communities’ and our national complacency with racialized poverty puts whole communities and the whole region in greater danger from climate crises. Hurricane Katrina was the clearest and most tragic illustration of that complacency and its real cost in dollars, in community trust and in lives.

The political and economic deprivation at the root of entrenched poverty stretches from the dislocation of Native peoples to enslavement and disenfranchisement of African Americans through the exploitation of poor Appalachian communities and continues today in the marginalization of Hispanic immigrant communities, among other ways. Our national economy has prospered and continues to prosper as a result of these forms of marginalization, and we share responsibility for making it right nationally – all of us.

Southern communities need to be whole in order to remain resilient in the face of ongoing climate crises – culturally, socially, economically and politically. Philanthropy within and outside the South has a key role to play in supporting Southern leaders who seek to build that community cohesion necessary to overcome environmental threats. When foundations prioritize protecting communities from climate shocks, those communities will be empowered to lead on other environmental goals like protecting physical ecosystems and regulating harmful industries. In the end, environmental self-determination is the most sustainable and effective path to climate resilience.

For all the challenges Southern communities have faced, and for all the deep personal and communal wounds that persist because of the region’s history of racial oppression and violence, the more than 100 interviews that informed this research echoed two refrains: Southerners take care of each other, and Southerners are deeply, personally invested in their home – in their land.

That history of mutual aid and rooted community life is, as with most things, complicated. But the truth it holds represents perhaps one of the South’s most valuable assets given the growing threat climate change presents. Climate change is already deeply, irrevocably affecting Southern communities – especially poor communities and communities of color that were relegated for centuries to land most vulnerable to flooding, pollution and dislocation. And just as these vulnerable communities have for centuries made a way with what they have, Southerners are on the leading edge of developing new ways to live together with each other and with our changing climate.

Climate change resilience work is inherently and fundamentally intersectional in the South. Southerners understand that the same moneyed power players who profit from extraction and exploitation of the physical environment also profit from artificially cheap labor, from private prisons and from other ways of exploiting human resources. What’s needed is a comprehensive strategy to build the power of grassroots organizations that truly represent the communities they serve to challenge this entrenched status quo.

Grassroots leaders like Naeema Muhammad, Rev. Mac Legerton and Donna Chavis are fusing environmental, economic and racial justice strategies to seek a holistic solution to the challenges their communities face. Deeply rooted funders like Mikki Sager, Liza Cowan and Erika Wright are leveraging the capital at their disposal to build the nonprofit infrastructure needed to sustain grassroots power. And larger national funders like Chantel Rush and the Kresge Foundation are trying out bold new strategies informed by their grassroots partners, bringing to bear their expertise and immense resources.

It is time for other foundations – both in the South and nationally – to meet these pioneers where they are and bring their own resources to the table. Any funder concerned about health, economic prosperity, access to opportunity or the physical and spiritual survival of coastal communities can and must find a way to invest in Southern climate resilience.

PRACTICAL TIPS FOR FOUNDATIONS AND DONORS FOR GREATER IMPACT IN THE SOUTH

Based on conversations with nonprofit leaders, advocates and funders across the South, there are certain characteristics foundations need to look for when they seek a Southern organization that will leverage philanthropic investments for greater impact. And there are some qualities that funders over-emphasize in their search for Southern partners, to the detriment of the foundation, grantee and community.

DO’S:

1. Do make sure you have “skin in the game.”

1. Do make sure you have “skin in the game.”

The work of building effective, long-term relationships of trust in cross-sector, cross-issue, cross-constituency coalitions to meet the climate change challenge head-on is difficult, and it is perceived as too risky for many potential partners to engage in the first place. Funders interested in real impact need to commit significant resources –financial, human or otherwise – to signal to other partners that they can trust funders’ long-term, deep engagement.

2. Do seek to understand the holistic history of Southern communities’ relationship to the land.

2. Do seek to understand the holistic history of Southern communities’ relationship to the land.

Land is the South’s most basic and abundant natural resource. National funders and even Southern foundations need to understand the complicated history of land use, allocation and dispossession in Southern communities in order to support a holistic environmental justice strategy.

3. Do look to intermediaries as key partners in making your investments more accessible to grassroots grantees.

3. Do look to intermediaries as key partners in making your investments more accessible to grassroots grantees.

Absorbing capital on the scale required by even midsized foundations is a significant challenge for many grassroots partners. The right intermediaries are high-leverage investments that build out the sustainability and capacity of Southern organizations and build a bridge between those organizations and direct funding streams.

DON’TS:

1. Don’t rely only on established funding streams to well-resourced Southern organizations.

1. Don’t rely only on established funding streams to well-resourced Southern organizations.

The environmental nonprofit subsector is infamously over-concentrated in a few organizations, which is as true in the South as it is nationally. Instead of only funding established organizations with long track-records, seek out ways to build new funding streams to new grantees. Working with good intermediaries or collaborating with other foundations to pool resources is one effective strategy.

2. Don’t dismiss existing infrastructure.

2. Don’t dismiss existing infrastructure.

When funders decide existing nonprofit infrastructure does not meet their needs and instead build something new to their designs, it undermines Southern capacity and autonomy, and frustrates key local partners and efforts. Funders must recognize existing social change infrastructure – both formal and informal – and increase their investments in making that infrastructure more representative, inclusive and effective rather than starting their own.

3. Don’t expect to be in the driver’s seat.

3. Don’t expect to be in the driver’s seat.

Funders bring substantial financial resources, human capital and significant expertise to the complicated, cross-issue challenge of climate change. But when they expect to drive the process of developing and executing on a holistic strategy to address that challenge, they displace and disrespect community expertise and community voices. Be humble; bring all the resources you have at your disposal to help solve the problem but let communities most affected by environmental issues lead.

Photo by Gaut.Chris, used under Creative Commons license.

Are you ready to engage in high-impact philanthropy in the South? Here are a few recommendations to guide the way:

1. Identify opportunities to fund climate, economic and social resilience and solutions in the South within current grantmaking priorities or expand priorities to include those strategies.

| How to Start | Who Can Help |

|

|

2. Deploy your financial, human and political capital to ensure underrepresented communities – those most impacted by environmental injustice – are meaningful partners in climate resilience conversations.

| How to Start | Who Can Help |

|

|

3. Seek reparative, healing, honest relationships between grantee and grantor and within grantee communities.

| How to Start | Who Can Help |

|

|

4. Make a healthy, resilient social change infrastructure a strategic priority.

| How to Start | Who Can Help |

|

|

WHAT’S NEXT?

Southerners understand how to build resilience and address the environmental challenges they face because of natural disasters and unjust environmental policies. But as communities build power and resilience, and people migrate to the South, especially to cities – from the rural South, the North and other parts of the world – communities are changing quickly and cities are expanding. Reactionary policies can quickly stifle the voices and the power in these communities.

How can foundations and donors support communities in building movements to address a changing urban South? Find out in the next report in the As the South Grows series, which will explore how communities are building movements and working toward an equitable and prosperous future in Atlanta.