CONTACT (S): Russell Roybal rroybal@ncrp.org

Elbert Garcia, egarcia@ncrp.org

NCRP: Philanthropy Must Play An Active Role in Reparations for Black People

Cracks in the Foundation: Philanthropy’s Role in Reparations for Black People in the DMV, the newest report from

the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, examines grantmakers’ role in repairing the harm

created by the wealth generated from the systemic exclusion and exploitation of Black people in the Washington, DC area.

WASHINGTON, DC – At a time when so many are willing to give up any discussion of America’s past in exchange for a false semblance of civil discourse, a new report from the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy makes the case that foundations have an immediate opportunity and responsibility to address society’s past harm in order to help communities heal and thrive.

Cracks in the Foundation: Philanthropy’s Role in Reparations for Black People in the DMV details how the disparities in areas like education, income, employment and housing for Black residents in the District of Columbia, southern Maryland, and northern Virginia areas (commonly known as the DMV) are not random or natural occurrences but are a string of conscious choices that repeatedly harmed communities.

Using publicly available quantitative and qualitative research, the report details how the great wealth that later made philanthropy possible in the DC area came at the expense of the social stability and economic success of Black residents. The report examines these harmful actions in four distinct sectors: media, housing, employment, and healthcare. It also provides a framework for foundations to not only understand their past, but how they may start acknowledging and addressing these harms with community residents.

The report is available for download at ncrp.org/reparations

“Despite individuals and some organizations being generally aware of the historical exploitation of Black people in this country, philanthropy has never really reckoned with how the ill-gotten gains from systemic discrimination and exclusion were the seed capital for so many modern grantmakers,” said Dara Cooper, a national strategic consultant and organizer. “This report helps us connect the voices of the past with the data of the present in order to give foundations little excuse to address and redress historical and ongoing exploitation of Black DMV residents and families.”

“We hope that foundations in the DC area will acknowledge these stories of harm and use the tools included in this report to establish and deepen connections with local groups and organizations and contribute financial resources and social capital for reparative action,” said NCRP President and CEO Aaron Dorfman. “These collective efforts are crucial for the immediate and long-term healing of impacted Black communities in the region.”

Regional funder if, A Foundation for Radical Possibility, is one of eight foundations included in the report as illustrative of the role that the sector has historically played in the systemic limiting of opportunities of local Black residents. They provided the lion’s share of funding for the report soon after embarking on their own journey into the foundation’s wealth generation and past actions.

“This report illustrates if’s commitment to racial justice, which requires accountability for injustice, both past and present. We are holding ourselves accountable for the harm we have caused,” said if Co-CEOs, Hanh Le and Temi F. Bennett. “Addressing anti-Blackness is ground zero for racial justice in America. Given the backlash to the alleged “racial reckoning” of 2020, our sector is in fight or flight mode. if is fighting, always. We invite others to join us.”

Although discussions about reparations for Black people have existed since the U.S. Civil War, the current movement for reparations has picked up steam in recent years with cities like Evanston, Ill. and states like California creating their own commissions and reports to help quantify the harm done and propose healing solutions. In philanthropy, recent articles by the BridgeSpan Group and Liberation Ventures and webinars by Justice Funders, Philanthropy Northwest and Decolonizing Wealth have made additional cases for reparations role in building a culture of repair and redress as foundations more deeply explore the impact of their initial seed capital.

Local organizers, like DC Movement for Black Lives Policy Table Coordinator Christian Beauvoir, see foundations’ role in reparations both as natural moral and practical extensions of their charitable missions.

“Every institution that claims to value Black people has a responsibility to make right every time that it has not,” said Beauvoir. “But reparations is more than just a legal framework for responding to harm. It says I see the violence that your ancestors endured when they deserved care, I see the discrimination they experienced when they deserved homes, schools, or doctors and because these histories still live in your DNA and in the institutions that surround you, I am committed to repairing what I have destroyed.”

“Philanthropy’s history of wealth generation presents a unique opportunity and responsibility,” says report author and NCRP Research Manager for Special Projects Katherine Ponce. “We hope this report and its community-centered research framework persuades – and, if necessary, pressures — decision-makers to shifting social and economic resources back to those whose rights, livelihoods and safety have been unjustly stripped away through historical actions reflecting structural anti-Black racism.”

The Need to Acknowledge and Address Past Harm Directly

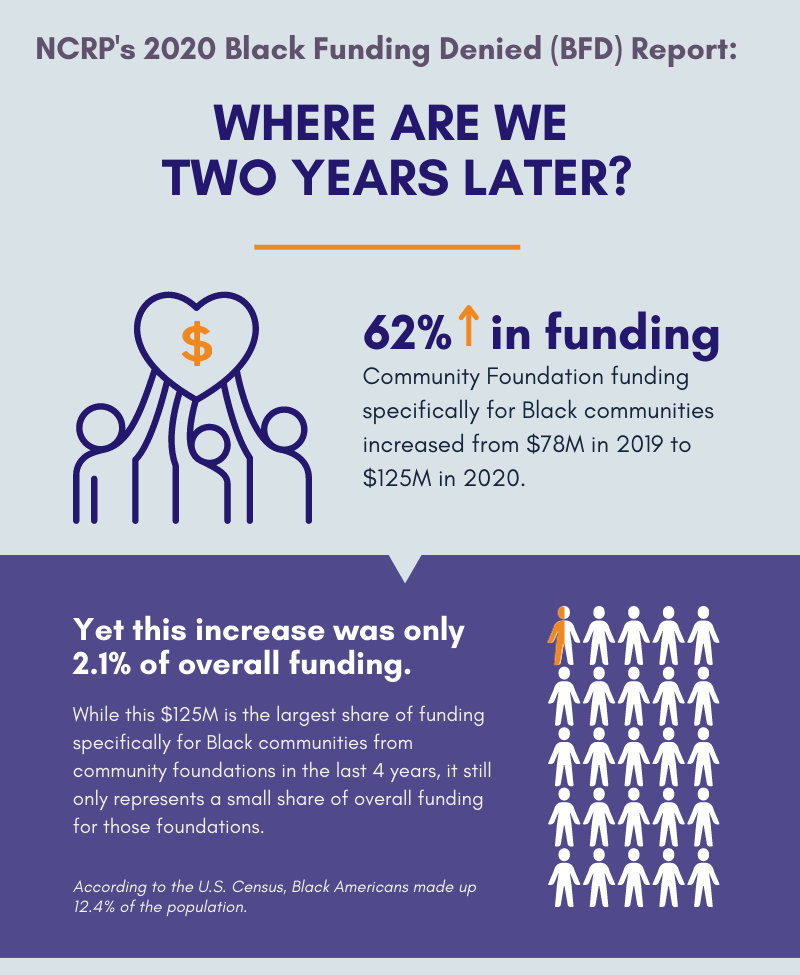

Past research by NCRP and others have noted philanthropy’s general underfunding of Black communities and Black-led institutions and non-profits. Yet increased funding to Black communities and racial justice work – while critical – is not the same as reckoning with harm done to specific Black people through the wealth origins of an individual institution.

Cracks in the Foundation looks to catalyze that process by (re)centering the conversation on those most impacted and harmed back by the wealth that was directly and indirectly generated through systemic racism and discrimination.

“By compiling, contextualizing and publishing biographical and other historical information about the origins of philanthropic wealth, the stories of harm experienced by Black people become unavoidable and, more importantly, actionable – especially for funders with a commitment to racial equity or racial justice,” writes Ponce. “Research that connects and centers stories of local Black communities can generate energy, opportunities, and concrete actions for foundations to engage in reparations and healing efforts. This report is both an invitation and a roadmap for local foundations – studied and otherwise – to do exactly that.”

DC native and NCRP Board Chair Dr. Dwayne Proctor sees the report as a crucial tool for funders to both address past harms and create a more equitable future for everyone.

“This report speaks to generations of history of Black people in the region and the throughlines to their oppression. I am encouraged to read a report that not only tells these stories but applies them to new and tested frameworks,” said Dr. Proctor, who also services as the President and CEO of the Missouri Foundation for Health. “If readers can connect the overlaps between the social determinants of health and the necessary healing of Black families today – real and transformative conversations about repair can begin.”

Local Feedback and Input

Ponce and NCRP researchers consulted with local academics, community leaders and oral history experts like the DC History Center. In cases where researchers could connect sufficient public evidence to a specific foundation, NCRP offered those foundations an opportunity to respond and identify current levels of related funding.

For previous Horning Family Foundation Board Member Andy Horning, conversations into the past are both personal and professional as the family foundation wades through a year of reflection and paused operations. As place-based foundation whose grantmaking is explicitly dedicated to centering Black people and Black communities in Washington, DC, he understands that there is no way around the vulnerability that comes with facing and doing something about the past.

“For white people, undoing racism and understanding white supremacy is a critical first step when they engage in philanthropy. It isn’t easy work,” says Horning. “Expect a direct challenge to who you are and have seen yourself to be. It requires incredible courage to step forward into the discomfort AND deep self-compassion when it inevitably becomes difficult. Its a reckoning, a grappling with the hard new reality of understanding ourselves and the world white supremacy has created.”

Dorfman acknowledges that the report will be uncomfortable even to the most progressive leaders and board members.

“We understand that for many organizations, this report will be personal. Founder legacies are complicated and this kind of reckoning process forces everyone connected to a foundation to be vulnerable,” says Dorfman. “But we also hope that foundations both mentioned and unmentioned will seize the chance to not only to exercise responsibility, but to also provide courage to those in their sector who may want to act, but do not know where to start.”

Although the report’s immediate focus is the Washington, DC area, the report’s methodology and recommendations can also serve as a model for funders and organizers in other cities and regions. The framework, community-centered process, and suggested actions also have potential applications not just for philanthropy, but for any institution in the public or private sector grappling with these uncomfortable, but necessary questions.

“This research stands on the shoulders of the generations of advocates that have been dreaming and implementing interventions in philanthropy that disrupt and transform the status quo,” says Jennie Goldfarb, Director of Operations & Strategic Engagement at Liberation Ventures. “Right now, foundations have a chance to model holistic repair. This report is the first step and I’m so proud of everyone involved in bringing this across the finish line. My hope is it fuels a movement of funders committed to truth telling and being in right relationship with each other and the organizations they fund.”

ABOUT NCRP

The National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) has served as philanthropy’s critical friend and independent watchdog since 1976. We work with foundations, non-profits, social justice movements and other leaders to ensure that the sector is transparent with, and accountable to, those with the least wealth, power and opportunity in American society.

Our storytelling, advocacy, and research efforts, in partnership with grantees, help funders fulfill their moral and practical duty to build, share, and wield economic resources and power to serve public purposes in pursuit of justice.